Archivists and librarians rarely have the pleasure of receiving a new collection and opening boxes to find neatly organized and sorted files. We frequently come across materials which have absolutely nothing to do with the rest of the collection. While combing through folders of press clippings about the MIM I found the program of a performance in 1891 which, while not relating to the museum, was simply too good not to share on this blog.

For Americans of my generation and older, the name Buffalo Bill immediately evokes an image of life in the western United States during the 19th century. This is largely thanks to his large-scale productions of battles with native American Indians and his depiction in many western films.

Buffalo Bill, who’s name was William Frederick Cody, and his troupe of performers, including Sioux Indians, arrived in June of 1891 in Belgium. They performed multiple shows in the commune of Saint-Gilles where they also made camp.

Bill travelled with all his materials, including stands which could hold 15,000 spectators. We read that “The Sioux and the cowboys who compose the troupe of Buffalo Bill form two equal camps, in total 250 men. The warriors, horses and twenty buffalo are currently wintering in an old convent in Benfeld, near Strasbourg.”

Bill had also reportedly brought the brother and sister of Sitting-Bull along for the show as well as Indians known by the names: Kicking bear, The young man who is afraid of his horses, Long foot, The Apache wolf and Red Shirt. Of course the famous sharpshooter Annie Oakley was also featured.

The performance depicted the Native Americans attacking a farm followed by a battle between Buffalo Bill and Yellow Hand, the chef of the Sioux.

The popularity of these performances was evident from the numerous newspaper articles found in the Belgian press.

Now we come to the unexpected find in the MIM archives.

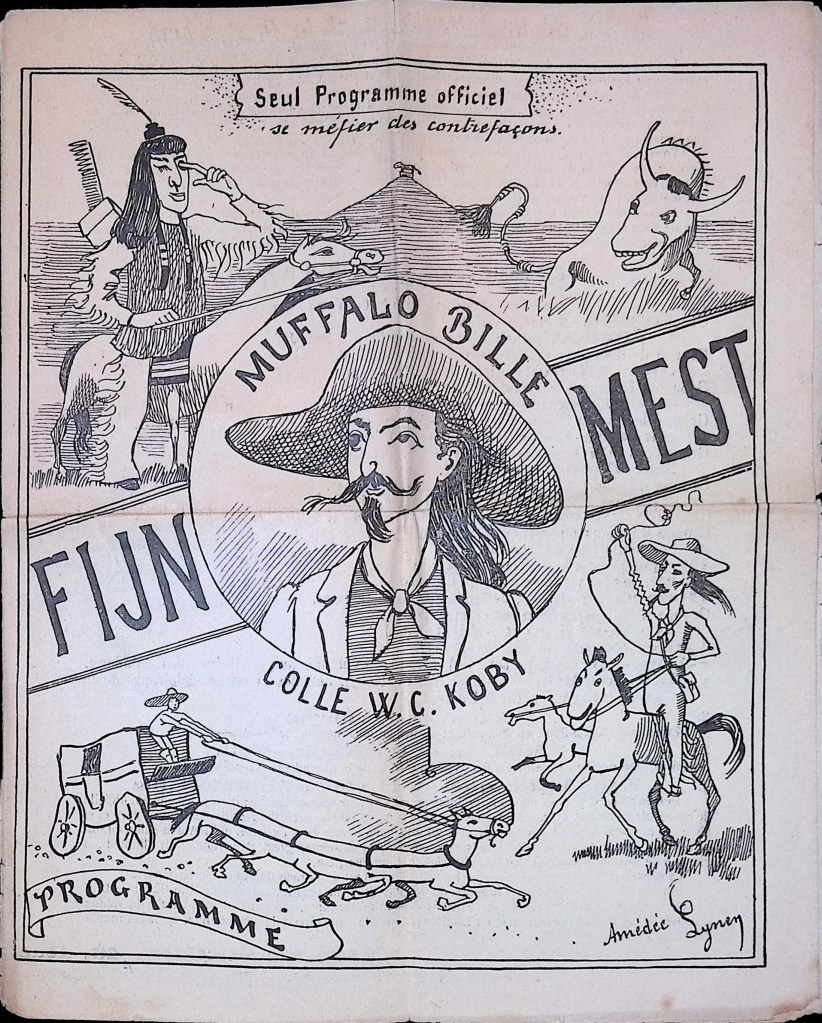

A few weeks after Buffalo Bill’s performance in Brussels a parody performance took place called “Muffalo Bille: Fijn Mest”, a play on “Buffalo Bill: Wild West”. Fijn Mest in Flemish translates to Fine Manure and it doesn’t take much imagination to understand the true meaning. On the cover of the program we see typical cowboy and Indian imagery with the exception of a buffalo on a hill reminiscent of the memorial in Waterloo.

The piece was reported to have been written by the Belgian artist Léon Herbo.

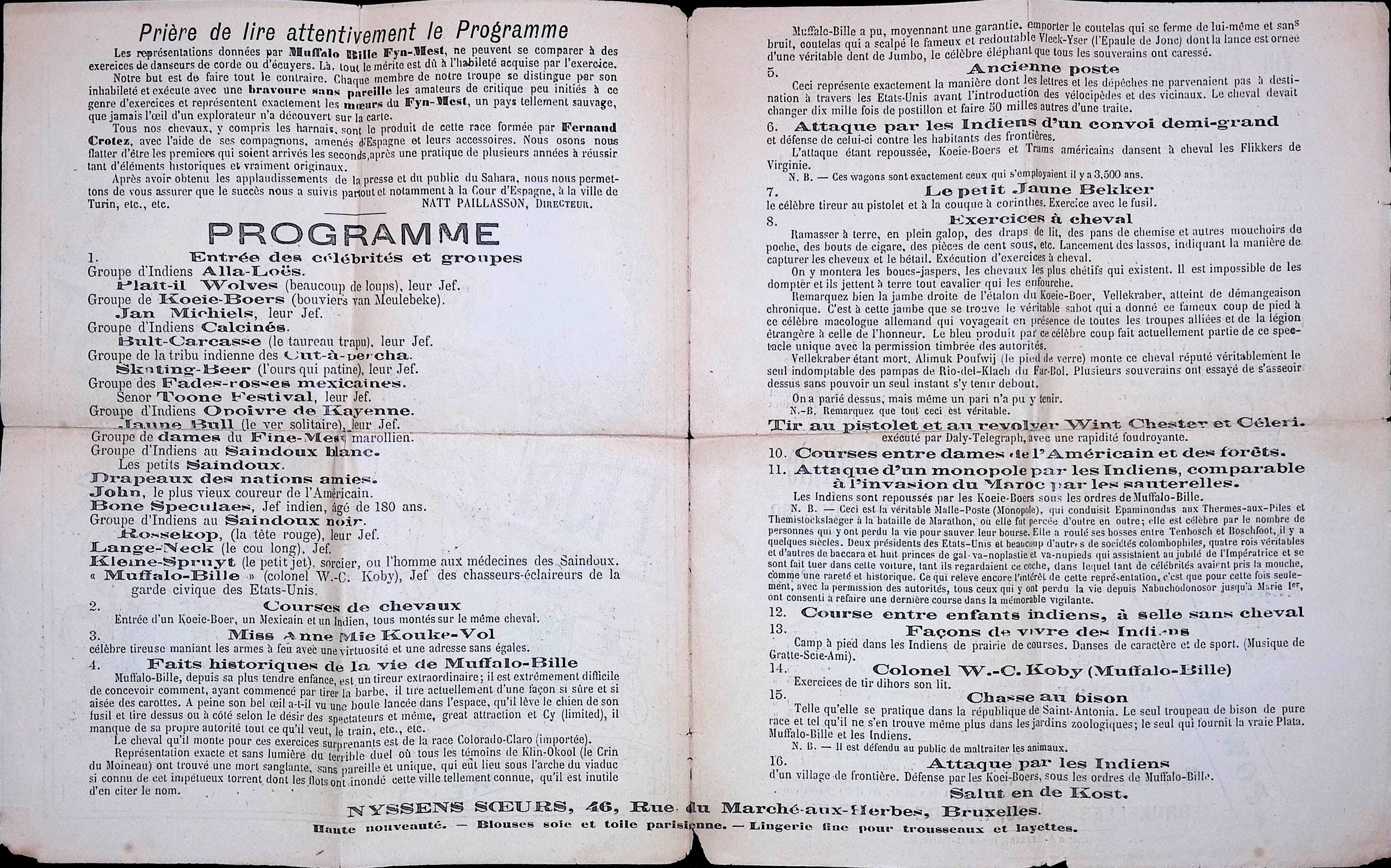

The program states, “The performances given by Muffalo Bille Fyn-Mest, cannot be compared to feats of rope dancers or squires. There, all the merit is due to the skill acquired by practice. Our aim is to do quite the opposite.”

The program is rife with parody of the American personalities and Belgian humor and is written in the Brusselian dialect which mixes French and Flemish.

We find the characters:

Plaît-il Wolves – Does he like wolves a parody of “The young man who is afraid of his horses”.

Koeie-Boers – a homonym for Cowboys who are described as cowherders from Meulebeke, a village in the “far west” of Belgium.

Calcinés – A tribe of Indians whose name translates to “burned”

Bult-Carcasse – Big-Carcass the leader of the Calcinés, this is a clear reference to Sitting-Bull who had been killed in 1890 by the US government.

Skating-Beer – A reference to Kicking Bear.

Jaune Bull – Yellow Bull a reference to both Yellow Hand and Sitting Bull

Groupe de dames du Fine-Mest marollien – A group of ladies from the Marolles in Fine-Manure. The Marolles is an area of Brussels where the working class lived, implying that the entire spectacle is a parody of Brussels.

Miss Anne Mie Kouke-Vol – This is a reference to Annie Oakley. The name refers to “hits a lot” but could also have meant “gets a lot of hits”.

There are doubtlessly numerous humorous references which have escaped my understand and I encourage the Belgian readers in particular to have a closer look.

The program ends with “Salut en de Kost” which basically means “Hope to never see you again”.

This sarcastic parody of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show was perhaps more of a commentary about the upper classes’ reception of “low-brow” entertainment in Brussels than of Bill’s show itself.

The program was found amongst the press clippings of Ernest Closson who would have been 20 years old at the time of Buffalo Bill and Muffalo Bille’s spectacles. Perhaps the future director of the museum attended the show, possibly with the intention of writing a review as he had recently begun his literary career.

Leave a comment