Between September 1935 and February 1938, Herman Closson conducted a long correspondence with the poet Alice Roux-Champion (1880-1956), the wife of the artist Victor-Joseph Roux-Champion (1871-1953). Madame Roux-Champion had recently become interested in cryptography and had published several articles presenting symbols which she had found in works of art such as the portrait of Antoine de Bourgogne by Rogier van der Weyden.

In this case, Roux-Champion claimed that she found the name “Corot” in the eyes of de Bourgogne.

The impetus of her correspondence with Closson was a violin by Gasparo Duiffopruggar (also known as Tieffenbrucker).

Roux-Champion contacted Closson to ask him to identify the “two” instruments seen in this drawing:

Her deduction that the bow of this stringed instrument was a separate instrument betrays her knowledge of musical instruments. Closson’s reply launched a lengthy correspondence which focused on her explanation of multiple discoveries of hidden symbols in works of art, and now musical instruments. She had a particular interest in the Duiffopruggar family of instrument makers and their connection to Leonardo da Vinci. In the portrait of Duiffopruggar seen above, Roux-Champion claimed that she could see “IV” in the leaves at the top of the frame, indicating that this is the fourth luthier of the Duiffopruggar family.

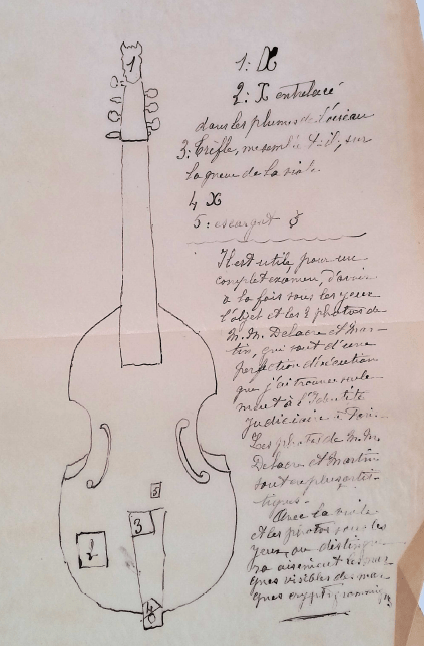

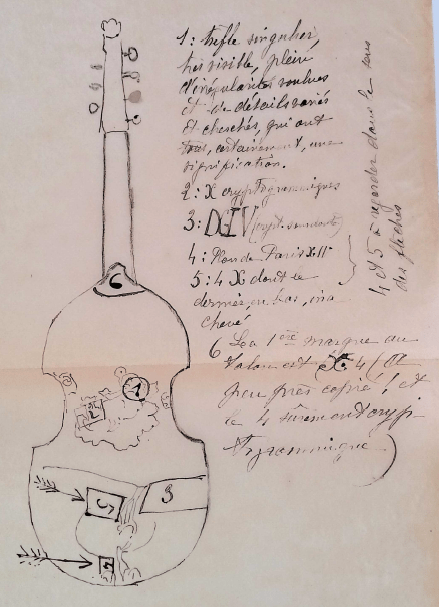

Roux-Champion’s correspondence included multiple photographs with her tracings which indicate where these secret marks could be found. Three of these photographs are of the famous viola da gamba in the MIM which is referred to as the “Plan de Paris” MIM-1427.

We see that Roux-Champion has found various marks such as “DG”, “DGIV”, “X”, clovers, snails, and even “Plan de Paris XIV”, all of which she claimed were hidden signatures of Duiffopruggar.

The note on the first tracing says:

It is very useful, in order to perform a complete examination, to have the object and the two photographs by Mr. Delacre and Martin at hand, [the photographs] are of a degree of execution which I have only found at the Institute Judiciaire in Paris. The photographs of Mr. Delacre and Martin are more artistic. With the viola da gamba and the photographs under your eyes, one can easily distinguish the visible cryptographic signs.

Closson replied that he was not able to find any of these signs, with the exception of two carved snails on the pegbox of the instrument.

One is left wondering how Roux-Champion found these secret symbols in these works of art and instruments. In one of her letters, she explained her process. She was, in fact, studying stereographic photographs a process which had been recently revived in France using glass slides rather than photographs. In the case of the Duiffopruggar viola da gamba, it is clear that she was interpreting the windmills to the south-west of the map as the letter “X” as well as finding words in the clouds which form the upper part of the instrument’s back. Perhaps she found patters in the cracks of the varnish of the instrument or the photographic process had left traces which were not present on the instrument. The photographs which Roux-Champion sent to Closson are clearly not those which she used with her stereoscope.

Sadly, the “Plan de Paris” will not lead to hidden treasure but the correspondence of Roux-Champion and Closson gives us a unique view into the renown of the MIM as a center of knowledge on musical instruments and instrument making.

Leave a comment